Fracture Nomenclature for Pediatric Trochlear Head fractures

Hand Surgery Resource’s Diagnostic Guides describe fractures by the anatomical name of the fractured bone and then characterize the fracture by the Acronym:

In addition, anatomically named fractures are often also identified by specific eponyms or other special features.

For the Pediatric Trochlear Head Fractures, the historical and specifically named fractures include no fracture eponyms.

Fractures of the trochlea are extremely uncommon overall, and particularly in the pediatric population. These injuries are generally recognized as coronal shear fractures, and the most common mechanism of injury is a fall on an outstretched hand. Since younger children have a higher range of elbow hyperextension, this mechanism is more likely to transfer the axial load to the posterior humerus and cause a supracondylar humeral fracture rather than a trochlear fracture. Pediatric trochlear fractures also rarely occur in isolation because the bone has no ligamentous or muscular attachments and is located deep within the elbow joint, thereby protecting it from direct trauma. Most of these injuries are instead accompanied by elbow dislocation, ligamentous injury, and/or fractures of the radial head, capitellum, or olecranon. Surgical intervention is necessary for most pediatric trochlear fractures and usually consists of open reduction and internal fixation.1-4

Definitions

- A pediatric trochlear fracture is a disruption of the mechanical integrity of the trochlea.

- A pediatric trochlear fracture produces a discontinuity in the trochlear contours that can be complete or incomplete.

- A pediatric trochlear fracture is caused by a direct force that exceeds the breaking point of the bone.

Hand Surgery Resource’s Fracture Description and Characterization Acronym

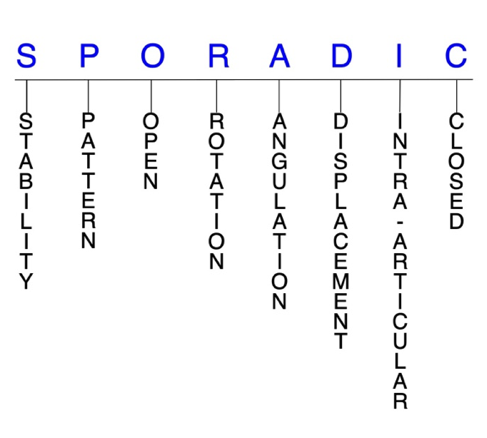

SPORADIC

S – Stability; P – Pattern; O – Open; R – Rotation; A – Angulation; D – Displacement; I – Intra-articular; C – Closed

S - Stability (stable or unstable)

- Universally accepted definitions of clinical fracture stability are not well defined in the literature.5-7

- Stable: fracture fragment pattern is generally nondisplaced or minimally displaced. It does not require reduction, and the fracture fragments’ alignment is maintained by with simple splinting or casting. However, most definitions define a stable fracture as one that will maintain anatomical alignment after a simple closed reduction and splinting. Some authors add that stable fractures remain aligned, even when adjacent joints are put to a partial range of motion (ROM).

- Unstable: will not remain anatomically or nearly anatomically aligned after a successful closed reduction and immobilization. Typically, unstable pediatric trochlear fractures have significant deformity with comminution, displacement, angulation, and/or shortening.

P - Pattern8-10

- No classification system has been created specifically for pediatric trochlear fractures, but the classification system for pediatric capitellar fractures may be used during diagnosis since the trochlea is involved in some of these fracture patterns:

- Type I (Hahn-Sternthal): shear fracture involving most of the capitellum and little or none of the trochlea; the fracture fragment has a significant bony component; this pattern is common in children

- Type II (Kocher-Lorenz): osteochondral fracture involving a variable amount of articular cartilage of the capitellum with minimal attached subchondral bone; this pattern is very rare in children

- Type III (Broberg-Morrey): comminuted or compression fracture of the capitellum

- Type IV (McKee): shear coronal fracture of the distal humerus involving the capitellum and a large portion of the trochlea

O - Open

- Open: a wound connects the external environment to the fracture site. The wound provides a pathway for bacteria to reach and infect the fracture site. As a result, there is always a risk for chronic osteomyelitis. Therefore, open fractures of the trochlea require antibiotics with surgical irrigation and wound debridement.5,11,12

R - Rotation

- Pediatric trochlear fracture deformity can be caused by proximal rotation of the fracture fragment in relation to the distal fracture fragment.

- Degree of malrotation of the fracture fragments can be used to describe the fracture deformity.

- Fracture fragments in pediatric trochlear fractures are typically rotated internally.13

A - Angulation (fracture fragments in relationship to one another)

- Angulation is measured in degrees after identifying the direction of the apex of the angulation.

- Straight: no angulatory deformity

- Angulated: bent at the fracture site

D - Displacement (Contour)

- Displaced: disrupted cortical contours

- Nondisplaced: ≥1 fracture lines defining one or several fracture fragments; however, the external cortical contours are not significantly disrupted

- Fracture fragments in pediatric trochlear fractures are typically displaced proximally.13

I - Intra-articular involvement

- Intra-articular fractures are those that enter a joint with ≥1 of their fracture lines.

- All pediatric trochlear fractures are considered intra-articular fractures.13

- Isolated trochlear fractures can have fragment involvement with the ulnohumeral joint, while concomitant fractures with the capitellum can also involve the radiocapitellar joint.

- If a fracture line enters a joint but does not displace the articular surface of the joint, then it is unlikely that this fracture will predispose to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. If the articular surface is separated or there is a step-off in the articular surface, then the congruity of the joint will be compromised, and the risk of post-traumatic osteoarthritis increases significantly.

C - Closed

- Closed: no associated wounds; the external environment has no connection to the fracture site or any of the fracture fragments.4-6

Related Anatomy13-17

- The elbow is a hinge-type synovial joint comprised of the radius, ulna, and humerus, and formed by three articulations: the ulnohumeral joint, radiocapitellar joint, and proximal radioulnar joint.

- The ulnohumeral joint is a hinge joint in which the trochlear notch (or semilunar notch) of the ulna articulates with the trochlea of the humerus. This joint allows for elbow flexion and extension.

- The trochlea is the medial portion of the articular surface of the distal humerus, which is contained between the lateral and medial columns of the elbow and is primarily covered with articular cartilage. It has medial and lateral ridges with an intervening trochlear groove.

- The radiocapitellar joint is the articulation of the radial head with the capitellum of the humerus. It is essential to elbow longitudinal and valgus stability and has an integral relationship with the lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

- The capitellum is a smooth, round, hemispheric structure that represents a portion of a forward-and downward-projecting sphere and which forms the anterior and inferior articular surface of the distal humerus. It is covered with articular cartilage on its anterior and inferior sides, but not its posterior side.

- The capitellum ossifies around 1 year of age and the lateral portion of the trochlea ossifies at 7 years. The capitellum and trochlea usually fuse at 12 years, but this may occur as early as 9 years. This combined ossification center fuses with the lateral epicondyle around this time to form the main body of the distal humeral epiphysis, which attaches to the metaphysis of the humerus between 12–13 years of age.

- The key ligaments of the elbow include the LCL (which extends from the lateral epicondyle and blends with the annular ligament of the radius), the medial collateral ligament (MCL, which originates from the medial epicondyle and attaches to the coronoid process and olecranon of the ulna), and the annulus ligament of the radius (which encircles the radial head and stabilizes the radial notch).

- The key tendons of the elbow include the tendons associated with the biceps, triceps, extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) muscles.

Incidence

- Pediatric trochlear fractures are extremely uncommon—especially in skeletally immature children—and their exact prevalence is unknown. Most documented reports are relegated to case reports and small case series.1,2