Fracture Nomenclature for Radial Head fractures

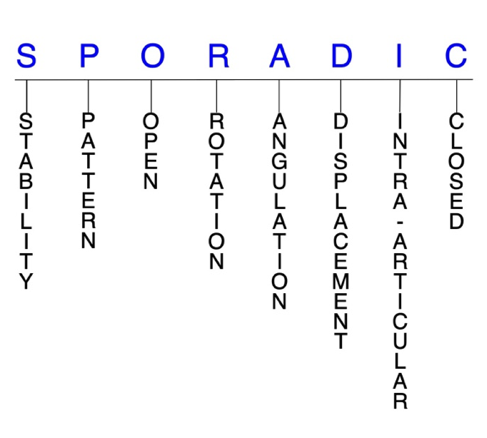

Hand Surgery Resource’s Diagnostic Guides describe fractures by the anatomical name of the fractured bone and then characterize the fracture by the Acronym:

In addition, anatomically named fractures are often also identified by specific eponyms or other special features.

For the Radial Head Fractures, the historical and specifically named fractures include:

Essex-Lopresti injury (ELI)

Terrible Triad Injury (TTI) of the elbow

By selecting the name (diagnosis), you will be linked to the introduction section of this Diagnostic Guide dedicated to the selected fracture eponym.

Fractures of the radial head are the most common of all injuries to the elbow, accounting for nearly one-third of all elbow fractures. These fractures result from direct or indirect trauma to the elbow, most frequently from a fall onto an outstretched hand (FOOSH) with the elbow partially flexed and pronated. Although isolated radial head fractures are possible, they are more likely to occur with associated injuries, particularly elbow dislocations, capitellar fractures, and medial collateral ligament (MCL) tears. Nonoperative treatment is generally indicated for most isolated, stable, and nondisplaced-to-minimally displaced fractures, while surgery is typically required for unstable fractures, displaced fractures, and those that fail conservative management.1-5

Definitions

- A radial head fracture is a disruption of the mechanical integrity of the radial head.

- A radial head fracture produces a discontinuity in the radial head contours that can be complete or incomplete.

- A radial head fracture is caused by a direct force that exceeds the breaking point of the bone.

Hand Surgery Resource’s Fracture Description and Characterization Acronym

SPORADIC

S – Stability; P – Pattern; O – Open; R – Rotation; A – Angulation; D – Displacement; I – Intra-articular; C – Closed

S - Stability (stable or unstable)

- Universally accepted definitions of clinical fracture stability are not well defined in the literature.6-8

- Stable: fracture fragment pattern is generally nondisplaced or minimally displaced. It does not require reduction, and the fracture fragments’ alignment is maintained by with simple splinting or casting. However, most definitions define a stable fracture as one that will maintain anatomical alignment after a simple closed reduction and splinting. Some authors add that stable fractures remain aligned, even when adjacent joints are put to a partial range of motion (ROM).

- Unstable: will not remain anatomically or nearly anatomically aligned after a successful closed reduction and immobilization. Typical unstable radial head fractures have significant deformity with comminution, displacement, angulation, and/or shortening.

- Unstable radial head fractures—such as fracture-dislocations—require restoration of radiocapitellar contact through radial head repair or reconstruction.1

P - Pattern1,9

- Type I: nondisplaced or minimally displaced (< 2 mm) fracture of the radial head or neck

- Type II: displaced (>2 mm) and angulated fracture of the radial head or neck

- Type III: severely comminuted fracture involving the entire radial head and neck

- Type IV: radial head fracture with associated elbow dislocation

O - Open

- Open: a wound connects the external environment to the fracture site. The wound provides a pathway for bacteria to reach and infect the fracture site. As a result, there is always a risk for chronic osteomyelitis. Therefore, open fractures of the radial head require antibiotics with surgical irrigation and wound debridement.6,10,11

R - Rotation

- Radial head fracture deformity can be caused by proximal rotation of the fracture fragment in relation to the distal fracture fragment.

- Degree of malrotation of the fracture fragments can be used to describe the fracture deformity.

A - Angulation (fracture fragments in relationship to one another)

- Angulation is measured in degrees after identifying the direction of the apex of the angulation.

- Straight: no angulatory deformity

- Angulated: bent at the fracture site

- Type II radial head fractures are angulated.12

D - Displacement (Contour)

- Displaced: disrupted cortical contours

- Nondisplaced: ≥1 fracture lines defining one or several fracture fragments; however, the external cortical contours are not significantly disrupted

I - Intra-articular involvement

- Intra-articular fractures are those that enter a joint with ≥1 of their fracture lines.

- Radial head fractures can have fragment involvement at the proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ) or radiocapitellar joint.

- If a fracture line enters a joint but does not displace the articular surface of the joint, then it is unlikely that this fracture will predispose to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. If the articular surface is separated or there is a step-off in the articular surface, then the congruity of the joint will be compromised, and the risk of post-traumatic osteoarthritis increases significantly.

C - Closed

- Closed: no associated wounds; the external environment has no connection to the fracture site or any of the fracture fragments.4-6

Radial head fractures: named fractures, fractures with eponyms and other special fractures

Essex-Lopresti Injury

- The Essex-Lopresti injury (ELI) consists of a comminuted radial head fracture combined with a disruption of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) and a tear of the interosseous membrane (IOM).13

- A fracture-dislocation, dislocation, or triangular fibrocartilage complex tear may also occur in this injury pattern.14

- These injuries typically occur when a high-energy load is applied axially to the forearm, most often from a FOOSH.13

- ELIs are uncommon, with one study finding that they were present in only 4% of all radial head fractures.13 Many cases — up to two-thirds — are also unrecognized, usually due to a physician’s failure to perform a complete and thorough examination of the wrist and forearm.14

Imaging

- Radiology studies - X-ray

- Anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views of both the elbow and wrist should be performed, while comparison views of the contralateral wrist or elbow may also be helpful.14

- Magnetic resonance imaging - MRI without contrast

- May be performed due to its highest sensitivity for diagnosing IOM tears.4

Treatment14

- Surgery is typically required for these injuries, and surgical options include the following:

- Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF)

- Radial head replacement

- Radial head excision

- DRUJ reduction

- Wrist arthroscopy, debridement, and a joint leveling procedure (eg, ulnar shortening osteotomy)

- Interosseous ligament reconstruction

Complications

- Stiffness

- Infection

- Reduced elbow ROM

- Residual pain

- Elbow instability

- Nonunion

- Failure of fixation

Outcomes

- ELIs are often associated with unsatisfactory functional outcomes, and outcomes are typically worse with greater treatment delays.4,13

- Management of comminuted radial head fractures remains controversial, as fixation of more than three parts may lead to early failure of fixation, nonunion, and limited forearm rotation.13

Terrible Triad Injury of the Elbow

- The terrible triad injury (TTI) of the elbow involves a radial head fracture combined with an elbow dislocation and ulnar coronoid process fracture. This injury has earned its nickname because it is very challenging to treat successfully.13,15

- TTIs are typically caused by a high-energy FOOSH.13

- These injuries are relatively rare, accounting for about 8–11% of all elbow dislocations and 3–10% of all radial head fractures.13

Imaging

- Radiology studies - X-ray

- Magnetic resonance imaging - MRI without contrast

- Radiology studies - Computerized tomography (CT) scanning

Treatment

- TTIs nearly always require surgery, and most experts recommend early surgical intervention to improve the odds of a successful outcome.4,15

- Surgery typically includes radiocapitellar joint restoration and reattachment of the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), while coronoid fracture fixation and MCL repair may also be performed in some cases.13

- Several approaches can be used to address coronoid fractures in TTIs, and since there is no consensus on which approach is best, decisions should be made based on fragment size and fracture location.

- For comminuted radial head fractures, either fixation or artificial replacement can be performed.

Complications

- Elbow stiffness

- Heterotopic ossification

- Elbow joint pain

- Arthritis

- Instability

Outcomes

- TTIs are generally associated with poor long-term outcomes, as complications like stiffness, pain, arthritis, and joint instability are common and can delay recovery.4

- One study found that radial head replacement allowed for elbow stability to be achieved with comparable overall outcomes to fixation, but the study lacked data on long-term outcomes.13

Related Anatomy3,16-18

- The elbow is a hinge-type synovial joint comprised of the radius, ulna, and humerus, and formed by three articulations: the ulnohumeral joint, radiocapitellar joint, and PRUJ.

- The radiocapitellar joint is the articulation of the radial head with the capitellum of the humerus. It is essential to elbow longitudinal and valgus stability and has an integral relationship with the LCL.

- The radius consists of a rectangular epiphysis at its distal end, a long shaft, and a radial neck and head at its proximal end. The radial head is important because it influences all three elbow articulations. The stability of the radiocapitellar joint is based on the opposite congruity of the convex capitellum with the concave radial head. Articular cartilage covers this concave surface and at least an arc of ~280° around the rim of the radial head.

- The PRUJ is formed by the articulation of the radial head with the lesser sigmoid notch of the proximal ulna and is stabilized by the annular ligament.

- The key ligaments of the elbow include the LCL (which extends from the lateral epicondyle and blends with the annular ligament of the radius), the MCL (which originates from the medial epicondyle and attaches to the coronoid process and olecranon of the ulna), and the annular ligament (which encircles the radial head and stabilizes the PRUJ and radiocapitellar joint).

- The key tendons of the elbow include the tendons associated with the biceps, triceps, and extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) muscles as well as the common extensor tendon (the shared origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), extensor digitorum communis (EDC), extensor digiti minimi (EDM) and extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU)), and the common flexor tendon (the shared origin of the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis (FCR), palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS), and flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU)).

- The radius and ulna are also connected by a sheet of thick fibrous tissue called the IOM.

Incidence

- Radial head fractures are the most common elbow injuries, accounting for ~30% of elbow fractures and 1–4% of all fractures in adults.5,18

- Radial head and neck fractures are also responsible for about 0.2% of all visits to the emergency department.3

- The reported incidence of radial head fractures is between 2.5–2.8 per 10,000 individuals each year.3,4

- The average age of patients who suffer radial head fractures is 45 years.3

- Associated injuries are detected in about one-third of radial head fractures, with elbow dislocation occurring in up to 14% and ulnar fracture occurring in up to 12% of cases.3,4