Fracture Nomenclature for Finger Proximal Phalanx Fracture Pediatric

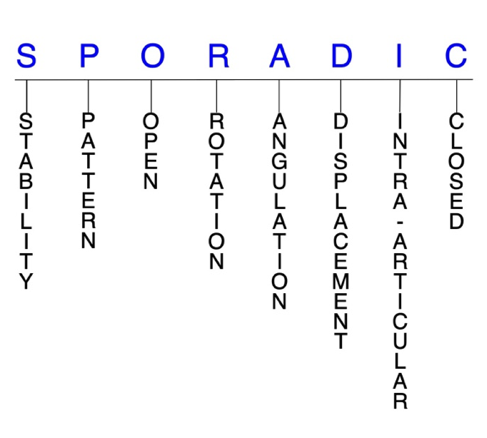

Hand Surgery Resource’s Diagnostic Guides describe fractures by the anatomical name of the fractured bone and then characterize the fracture by the Acronym:

In addition, anatomically named fractures are often also identified by specific eponyms or other special features.

For the Finger Proximal Phalanx Fracture Pediatric, the historical and specifically named fractures include:

Salter-Harris type II and juxta-epiphyseal fractures of the proximal phalanx base

MP joint dislocation with volar plate avulsion fracture

By selecting the name (diagnosis), you will be linked to the introduction section of this Diagnostic Guide dedicated to the selected fracture eponym.

The prevalence of hand fractures is extremely high in children, and the proximal phalanx is the most commonly fractured hand bone in the pediatric population. These fractures are twice as common as fractures of the other phalanges, and the base of the proximal phalanx is the most frequently fractured site, primarily due to Salter-Harris type II and juxta-epiphyseal fractures, usually in the little finger. Fractures of the proximal phalanx neck—which are practically exclusive to children—head/condyle, and shaft are less common but also occur in certain situations. The mechanism of injury for these fractures varies depending on the child’s age and may include crushing forces, falls, and sports participation. Although these injuries share some similarities with their counterparts in the adult population, the presence of physes and other developmental changes in children and adolescents warrants careful consideration of these factors to ensure appropriate diagnosis and management.1-5

Definitions

- A pediatric proximal phalanx fracture is a disruption of the mechanical integrity of the proximal phalanx.

- A pediatric proximal phalanx fracture produces a discontinuity in the proximal phalanx contours that can be complete or incomplete.

- A pediatric proximal phalanx fracture is caused by a direct force that exceeds the breaking point of the bone.

Hand Surgery Resource’s Fracture Description and Characterization Acronym

SPORADIC

S – Stability; P – Pattern; O – Open; R – Rotation; A – Angulation; D – Displacement; I – Intra-articular; C – Closed

S - Stability (stable or unstable)

- Universally accepted definitions of clinical fracture stability is not well defined in the hand surgery literature.6-8

- Stable: fracture fragment pattern is generally nondisplaced or minimally displaced. It does not require reduction, and the fracture fragments’ alignment is maintained with simple splinting. However, most definitions define a stable fracture as one that will maintain anatomical alignment after a simple closed reduction and splinting. Some authors add that stable fractures remain aligned, even when adjacent joints are put to a partial range of motion (ROM).

- Unstable: will not remain anatomically or nearly anatomically aligned after a successful closed reduction and simple splinting. Typically unstable pediatric proximal phalanx fractures have significant deformity with comminution, displacement, angulation, and/or shortening.

- In the pediatric population, even most displaced fractures are easily reduced closed and often quite stable.3

P - Pattern

- Proximal phalanx head: oblique, transverse, or comminuted; can involve the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint; these are intra-articular fractures that usually affect one or both condyles of the proximal phalanx head with or without displacement; displaced fractures can affect joint congruity.

- Proximal phalanx neck: fractures of the neck of the phalanges occur almost exclusively in children and are most common in the proximal phalanx; these fractures occur distal to the collateral ligament recess of the proximal phalanx, and presenting patients typically have apex volar angulation with associated sagittal and subcondylar malalignment.3,9,10

- Proximal phalanx shaft: transverse, oblique, or comminuted, with or without shortening; these fractures are less common than other proximal phalanx fractures, and clinical examination is necessary because very innocuous-looking injuries can have substantial rotational deformities that can lead to gripping problems.2,11

- Proximal phalanx base: the base is the most common site of injury, and these fractures typically occur when the finger is abducted past the normal range of the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint (Nellans); these are usually either Salter-Harris type II or juxta-epiphyseal base fractures, but the MP joint can also be involved.9,12

- These fractures may be intra- or extra-articular and usually involve the dorsal or volar lip of the proximal phalanx base.10

O - Open

- Open: a wound connects the external environment to the fracture site. The wound provides a pathway for bacteria to reach and infect the fracture site. As a result, there is always a risk for chronic osteomyelitis. Therefore, open fractures of the pediatric proximal phalanx require antibiotics with surgical irrigation and wound debridement.6,13,14

R - Rotation

- Pediatric proximal phalanx fracture deformity can be caused by rotation of the distal fragment on the proximal fragment.

- Degree of malrotation of the fracture fragments can be used to describe the fracture deformity; this is not a common type of fracture deformity in the pediatric proximal phalanx.

- Radial or ulnar deviation and malrotation of pediatric proximal phalanx neck fractures are also possible, and radiographs can underestimate the degree of clinical deformity.3

- Oblique fractures of the little finger are often malrotated, although physeal, transverse, intra-articular, and minor fractures by radiographic appearance can all be malrotated and lead to a rotated malunion.15

- Some pediatric proximal phalanx fractures will have substantial rotational deformities that can only be detected through clinical evaluation.11

- The MP joint is particularly prone to rotational injuries due to its mobility and the lever arm of the digit acting at the base of the proximal phalanx.16

A - Angulation (fracture fragments in relationship to one another)

- Angulation is measured in degrees after identifying the direction of the apex of the angulation.

- Straight: no angulatory deformity

- Angulated: bent at the fracture site

- Example: pediatric proximal phalanx neck fractures usually have apex volar angulation with associated sagittal and subcondylar malalignment.9

- Significant ulnar angulation can also result when the base of the little finger’s proximal phalanx is fractured.12

- Physeal arrest can result in difficult-to-treat angular deformities and joint malalignment due to continued growth in adjacent bones.11

D - Displacement (Contour)

- Displaced: disrupted cortical contours

- Nondisplaced: fracture line defining one or several fracture fragments; however, the external cortical contours are not significantly disrupted

- Pediatric proximal phalanx neck fractures are prone to proximal displacement, and most are displaced with dorsal translation and extension angulation.3,12

- Pediatric proximal phalanx shaft fractures tend to displace apex volarly.12

I - Intra-articular involvement

- Fractures that enter a joint with one or more of their fracture lines.

- Pediatric proximal phalanx fractures can have fragment involvement with the PIP or MP joints.

- If a fracture line enters a joint but does not displace the articular surface of the joint, then it is unlikely that this fracture will predispose to posttraumatic osteoarthritis. If the articular surface is separated or there is a step-off in the articular surface then the congruity of the joint will be compromised and the risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis increases significantly.

- Pediatric fractures of the proximal phalangeal condyles are intra-articular and can involve one or both condyles. Fracture patterns include lateral avulsion fractures, unicondylar or intracondylar fractures, bicondylar or transcondylar fractures, and shearing fractures.3

C - Closed

- Closed: no associated wounds; the external environment has no connection to the fracture site or any of the fracture fragments.6-8

Pediatric proximal phalanx fractures: named fractures, fractures with eponyms and other special fractures

Salter-Harris type II and juxta-epiphyseal fractures of the proximal phalanx base

- Salter-Harris type II and juxta-epiphyseal fractures represent two of the most common hand fractures in children, and the majority involves the proximal phalanx.1

- Salter-Harris II fractures are physeal, while in juxta-epiphyseal fractures, the fracture line is entirely metaphyseal and 1-2 mm distal to the physis. 17

- Several similarities exist between these two types of fractures, and there is ongoing debate as to which is more common.

- In one study of 100 boys and girls with proximal phalanx base fractures, the most common type of fracture was the juxta-epiphyseal type II fracture (53%) followed by the Salter-Harris II fracture (26%). This suggests that many of the pediatric proximal phalanx base fractures thought to be Salter-Harris II may actually be juxta-epiphyseal.17

- Both fractures appear to follow the same injury pattern: sudden ulnar or radial angulation of the finger and excessive abduction of the MP joint that separates a small fragment at the base of the proximal phalanx on the side of the angulation; the fracture line consequently either continues transversely through the physis or the metaphysis 1–2 mm distal to the physis.11,17

- The little finger is the most frequently involved digit of these fractures, followed by the ring finger. Fractures of the base of the little finger result from forced abduction and are termed “extra-octave” fractures to describe the extreme ulnar deviation that is typically present.12,17,18

Imaging

- PA, lateral, and oblique X-ray views are recommended.

Treatment

- Most mildly displaced Salter-Harris II and juxta-epiphyseal fractures are stable and can be treated with closed reduction.

- Reduction can be accomplished with the “pencil technique,” in which a pencil is placed within the web space adjacent to the fractured digit to serve as a fulcrum, and then pressure is applied to the proximal fragment while the shaft is brought radially. This maneuver will not correct sagittal malalignment, but in patients with ≥2 years of skeletal growth, sagittal malalignment remodels well.11,12

- Another option for closed reduction is to flex the MP joint to 90°, which tightens the collateral ligaments and thus stabilizes the proximal fragment. Reduction is then accomplished by pushing the distal fragment across into the correct alignment. In this technique, the MP joint is locked in 90° of flexion during manipulation, which helps correct any extension deformity.18

- Whichever technique of closed reduction is used, over-correction is generally recommended. The periosteal sleeve is usually intact on the side of the angulation and generally prevents over-reduction and provides stability in the reduced position.18

- Once the fracture is reduced, the finger should be splinted to the adjacent uninjured finger before an ulnar gutter splint is applied. This is especially important in ‘‘extra-octave’’ fractures, in which the pull of the abductor digiti minimi muscle tends to redisplace the fracture.18

- In severely displaced fractures, closed reduction and splinting can result in residual deformity and other long-term complications. Entrapment of flexor tendons—particularly the flexor digitorum profundus—is also associated with these fractures, which makes them additionally irreducible. Surgical intervention may therefore be necessary in these cases or when there is a disruption of the collateral ligaments or fracture comminution.1,11,12

- Open reduction and pinning is the preferred method of treatment in these cases, and an anatomic and stable reduction of the involved phalanx is very important in order to allow a proper gliding of the tendon.

- K-wire fixation may be needed in fractures that are extremely unstable.1

Complications

- “Pseudo-claw” deformity

- Residual deformity

- Stiffness

Outcomes

- If an anatomic and stable reduction is achieved through surgery, good functional and radiologic outcomes may be achieved.1

- Remodeling after juxta-epiphyseal fractures of the base of the proximal phalanx depends on several factors, including the age of the patient and degree and type of deformity.

- Remodeling is less likely to occur in adolescents than young children, and angulation in the same plane as the joint movement will usually correct with growth. Whereas if the angulation is in the opposite plane, or is rotational, it will not correct.18

- In one study of patients with juxta-epiphyseal fractures of the proximal phalanx base, 18 mildly displaced fractures were treated with closed reduction and splinting. This led to successful outcomes with no complications.

- In the 16 patients with severely displaced fractures, however, it was difficult to obtain an adequate reduction by closed techniques, and complications occurred. K-wire fixation was therefore necessary to maintain the reduction in 5 of these patients.18

- MP joint dislocation is not very common in the pediatric population, but it can be a serious injury that is typically associated with significant trauma. The index finger and thumb are the most commonly involved digits.19

MP joint dislocation with volar plate avulsion fracture

- These injuries are often the consequence of hyperextension and falls on an outstretched hand (FOOSH), and outdoor activities and sports are frequently responsible.20

- MP dislocations can be classified as simple or complex, with the latter involving soft tissue interposition between the articular surfaces of the joint.19

- Volar plate avulsion fractures are most commonly responsible for complex MP dislocations.20

- The volar plate attaches to the proximal phalangeal epiphysis in children, and when a finger is hyperextended, the proximal metacarpal attachment of the volar fibrocartilage ruptures away from the periosteal continuity, while the proximal phalanx is forced dorsally. This causes the metacarpal head to be displaced towards the palm, while the volar plate remains attached to the proximal phalanx and slips into the joint and becomes entrapped.20,21

Imaging

- AP, lateral, and oblique X-ray views are required to confirm the diagnosis. The lateral view is most helpful.

Treatment

- Most simple dorsal MP dislocations can be managed conservatively with closed reduction that includes distal traction and volar pressure on the dislocated bone, followed by splinting the joints in flexion.19

- Complex MP dislocations are often irreducible due to the soft tissue (eg, volar plate) that is trapped between the articular surfaces. Therefore, surgery is typically needed in these cases and whenever attempted closed reduction fails.19,21

- The surgical approach utilized can be dorsal, volar, or combined, and there is ongoing debate as to the optimal strategy. Surgeons must be mindful of the presence of osteochondral fragments that may require fixation or excision, depending on their size and location. 20,22

- The advantage of the volar approach is that it allows direct access to the lesion and repair of the volar plate, which decreases the risk of subsequent instability. The dorsal approach provides excellent exposure of the volar plate and access to the osteochondral fragments of the metacarpal head, but its main disadvantage is the longitudinal splitting of the volar plate to reduce the MP joint, which is irreparable.22

- The volar plate is incised to achieve reduction in the dorsal approach, while both the volar plate and natatory ligament are incised in the volar approach.20

- Incision of the volar plate releases tension in the accessory collateral ligament and allows the remainder of the volar plate to be reduced along the side to which the flexor tendons have shifted.21

- Extensive soft tissue release may not be necessary in pediatrics because of normally increased laxity of ligamentous structures. Only enough fibrocartilagenous plate or ligament should be incised to accomplish the reduction.21

- After surgery, early protected mobilization of the MP joint with a dorsal splint preventing full extension is needed.21

- Another surgical option for complex dorsal MP dislocations is arthroscopic reduction.22

- Internal fixation is unnecessary in these injuries, and it has been suggested that K-wires crossing the physis may be harmful in skeletally immature patients.21

Complications

- Premature physis closure

- Posttraumatic osteoarthritis

- Osteonecrosis

- Stiffness

- Loss of motion

Outcomes

- One study suggested that closed reduction is successful in about 50% of cases.19

- Findings from another study on patients ranging in age from 13-22 years showed that complex dorsal MP dislocations treated on the day of injury with dorsal or volar open reduction techniques can achieve good outcomes with no functional deficit, no pain, and minimal arthritis.20

Related Anatomy

- The pediatric proximal phalanx consists of a distal phalangeal head that articulates at the PIP joint with the middle phalanx, a supportive neck, a narrow diaphyseal shaft, a proximal metaphysis, and a base that articulates at the MP joint with the metacarpal. In developing children and adolescents, the epiphyseal plate is located at the base of the proximal phalanx, which has a dorsal and volar lip.9

- The ligaments associated with the proximal phalanx at the PIP and MP joints are the joint capsule, the proper and accessory collateral ligaments, the volar plates, the natatory ligament, and the transverse and oblique bands of the retinacular ligament. The oblique band originates on the lateral volar aspect of the proximal phalanx and attaches dorsally to the common extensor, while the transverse band originates and attaches closer to the joint line and inserts on the lateral border of the proximal phalanx.

- Tendon attachments of the proximal phalanx include the extensor digitorum tendon, the flexor digitorum superficialis, and a flexor sheath that attaches to the sides of the proximal phalanx.

- There is a basic anatomical difference between pediatric proximal and middle phalanges: the proximal phalanges have a longer, wider intramedullary canal with more cancellous bone, whereas the middle phalanges have a shorter, narrower intramedullary canal with more cortical bone. In general, fractures through cortical bone heal slower than fractures in cancellous bone.23

Incidence and Related injuries/conditions

- Metacarpal and phalangeal fractures account for about 21% of all pediatric fractures, and the phalanges are the most commonly injured hand bones in this population.9,10

- The annual incidence of phalangeal fractures in children and adolescents up to 19 years old is approximately 2.7%.24

- The proximal phalanx is the most frequently fractured phalangeal bone in the pediatric population. These fractures are about twice as common as those of the distal and middle phalanges.1,4,25

- The incidence of all phalangeal fractures is highest in children aged 10-14 years, which coincides with the time that most children begin playing contact sports.9

- Studies have also suggested that the older the child, the more proximal the fracture that is sustained, with proximal phalanx fractures being most common in adolescents. In addition, despite the fact that most patients are right-hand dominant, the distribution of phalangeal fractures is generally found to be similar in both the right and left hands.4,26

- Physeal injuries account for 15-30% of all pediatric fractures, and significant growth disturbance may occur in approximately 10% of cases. These types of injuries are most common during the adolescent growth spurt between ages 10-16, and are more common in boys than in girls.19