Fracture Nomenclature for Fracture Radius and/or Ulna and/or Both Forearm Bones Pediatric

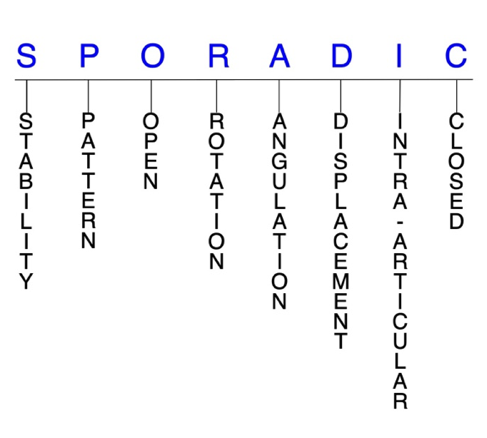

Hand Surgery Resource’s Diagnostic Guides describe fractures by the anatomical name of the fractured bone and then characterize the fracture by the Acronym:

In addition, anatomically named fractures are often also identified by specific eponyms or other special features.

For the Fracture Radius and/or Ulna and/or Both Forearm Bones Pediatric, the historical and specifically named fractures include:

Galeazzi fracture

Monteggia fracture

Greenstick fracture

By selecting the name (diagnosis), you will be linked to the introduction section of this Diagnostic Guide dedicated to the selected fracture eponym.

Forearm shaft fractures are the most common fracture type in the pediatric population. Although either the radial shaft or ulnar shaft can be fractured in isolation, both bones are usually injured simultaneously, which is referred to as a “both bone” forearm fracture. Males between the ages of 9-12 are at the greatest risk for forearm fractures, and the mechanism of injury usually involves indirect trauma, such as a fall on an outstretched arm (FOOSH) with a rotational component. Most pediatric patients are treated conservatively with closed reduction and immobilization, although surgical intervention may be indicated for those that fall out of specific parameters for acceptable alignment after reduction. The rate of surgery has also been increasing in recent years.1-4,28

Definitions

- Pediatric forearm fractures are a disruption of the mechanical integrity of the radial and/or ulnar shaft.

- Pediatric forearm fractures produce a discontinuity in the radial and/or ulnar shaft contours that can be complete or incomplete.

- Pediatric forearm fractures are caused by a direct force that exceeds the breaking point of the bone.

Hand Surgery Resource’s Fracture Description and Characterization Acronym

SPORADIC

S – Stability; P – Pattern; O – Open; R – Rotation; A – Angulation; D – Displacement; I – Intra-articular; C – Closed

S - Stability (stable or unstable)

- Universally accepted definitions of clinical fracture stability are not well defined in the literature.5-7

- Stable: fracture fragment pattern is generally nondisplaced or minimally displaced. It does not require reduction, and the fracture fragments’ alignment is maintained with simple splinting or casting. However, many definitions define a stable fracture as one that will maintain anatomical alignment after a simple closed reduction and splinting. Some authors add that stable fractures remain aligned, even when adjacent joints are put through a partial range of motion (ROM).

- Unstable: will not remain anatomically or nearly anatomically aligned after a successful closed reduction and immobilization. Typically unstable pediatric radial and ulnar shaft fractures have significant deformity with comminution, displacement, angulation, and/or shortening.

- An unstable ulnar shaft fracture is one that involves >50% displacement, >10° angulation, the proximal third of the bone, or which also features proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ) or distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) instability.8

P - Pattern

- Radial shaft

- Proximal third

- Middle third

- Distal third

- Apex volar

- Apex dorsal

- Ulnar shaft

- Proximal third

- Middle third

- Distal third

- Apex volar

- Apex dorsal

O - Open

- Open: a wound connects the external environment to the fracture site. The wound provides a pathway for bacteria to reach and infect the fracture site. As a result, there is always a risk for chronic osteomyelitis. Therefore, open pediatric forearm fractures require antibiotic treatment with surgical irrigation and wound debridement.5,9,10

- There is high risk for visible deformity and open injury in both bone forearm fractures due to the significant forces involved.11

R - Rotation

- Forearm fracture deformity can be caused by proximal rotation of the distal fracture fragments in relation to the proximal fracture fragments.

- Degree of malrotation of the fracture fragments can be used to describe the fracture deformity. In pediatric forearm fractures, this may be difficult to assess malrotation.3 Both bone forearm fractures are especially susceptible to rotational malalignment because the pronators and supinator muscles attach at different anatomic points on the radius and ulna, therefore, when a fracture occurs between these insertion sites, the muscles may pronate the distal fracture fragment while other muscles are supinating the proximal fracture fragments.

- Greenstick fractures (incomplete fractures of the diaphysis) tend to be stable but can be angulated, while complete fractures can be shortened, as well as rotated and angulated.4

A - Angulation (fracture fragments in relationship to one another)

- Angulation is measured in degrees after identifying the direction of the apex of the angulation.

- Straight: no angulatory deformity

- Angulated: bent at the fracture site

- There are various ways to describe angulation, but an easy way is to describe the amount of angulation in degrees and the direction of the angulation by stating which way the apex of the angulation is pointing. For example, the radius fracture was angulated 35 degrees with the apex pointing dorsally.

- Galeazzi fractures have been found to result in shortening and angulation, which is responsible for the disruption of the DRUJ.12

D - Displacement (Contour)

- Displaced: disrupted cortical contours

- Nondisplaced: one or more fracture lines define one or several fracture fragments; however, the external cortical contours of the bone are not significantly disrupted i.e., the fragments remain anatomically aligned.

I - Intra-articular involvement

- Intra-articular fractures are those that enter a joint with one or more of the fracture lines.

- Forearm fractures can have fragment involvement with the DRUJ, PRUJ, radiocarpal, humeroulnar, or humeroradial joints. Pediatric forearm fractures are more frequently associated with dislocations of proximal or distal radioulnar joints than with true intra-articular fracture patterns.

- If a fracture line enters a joint but does not displace the articular surface of the joint, then it is unlikely that this fracture will predispose to posttraumatic osteoarthritis. If the articular surface is separated or there is a step-off in the articular surface, then the congruity of the joint will be compromised and the risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis increases significantly.

C - Closed

- Closed: no associated wounds; the external environment has no connection to the fracture site or any of the fracture fragments.4-6

Pediatric forearm fractures: named fractures, fractures with eponyms and other special fractures

Galeazzi fracture

- Also known as a reverse Monteggia fracture or Piedmont fracture, the Galeazzi fracture is fracture of the middle to distal third of the radial shaft combined with a subluxation or dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ).12,13

- The Galeazzi fracture is considered a true forearm axis injury because of concomitant bone and soft tissue injuries. The triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) and/or interosseous membrane (IOM are particularly at risk and their injury can contribute to forearm instability.12,14

- These injuries typically result from direct impact to the radius with forearm pronation. When a patient sustains a radial shaft fracture in the middle to distal third of the bone, the possibility of an associated DRUJ injury should be investigated.12,14

- Galeazzi fractures are more common in pediatric patients than adults. In children and adolescents, they are usually caused by sports injuries, falls from a height, or motor vehicle accidents.11,13

Imaging13

- Radiology studies - X-ray

- Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views are usually sufficient, but an oblique view may help to better classify the injury and define a fracture line that is present but not apparent on the AP and lateral views.

- Because a coexistent joint injury is always possible, the distal wrist joint and elbow joint should always be included on the forearm X-rays or X-ray separately.

- Radiology studies - Computerized tomography (CT) scanning

- Not usually needed, but occasionally used to evaluate for nonunion or complex intra-articular fracture.

- Magnetic resonance imaging - MRI without contrast

- May be used in rare cases to detect TFCC tears and/or IOM disruption.

Treatment

Conservative

- The gold standard for pediatric Galeazzi fractures is conservative treatment, as these injuries are typically stable due to the high elasticity of the ligaments and superior DRUJ strength compared to adults, the thicker periosteum, and greater chances for fracture remodeling.15

- Treatment involves closed reduction performed under anesthesia, followed by above-elbow immobilization in supination with a cast or splint for up to 6 weeks.13,15

Operative

- Surgery is only indicated if closed reduction fails to elicit satisfactory alignment; if there is loss of reduction after the initial reduction or significant DRUJ instability .15

- Surgical options include K-wire fixation of the DRUJ, flexible intramedullary nailing, plate osteosynthesis, or open reduction without internal fixation. The preferred approach should be determined based on patient age, fracture location, and DRUJ stability after reduction.15

Complications

- Nonunion

- Malunion

- DRUJ instability

- Reduced grip strength

Outcomes

- Children generally report better long-term outcomes than adults, and several studies have shown that conservative treatment can lead to successful results.13,15

Monteggia fracture

- A Monteggia fracture involves a fracture of the proximal third of the ulna combined with a subluxation or dislocation of the radial head at the proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ) and the humeroradial joint.1,11,12

- These injuries most commonly occur secondary to a direct blow to the posterior aspect of the ulna, with the elbow extended and the forearm in hyperpronation.16,17

- Monteggia fractures account for <2% of all forearm fractures and are more common in pediatric patients than adults. In children and adolescents, they are usually caused by sports injuries, falls from a height, or motor vehicle accidents.11,13,16

Imaging17

- Radiology studies - X-ray

- AP and lateral orthogonal views with an oblique view are usually adequate.3

- Sonographic studies - Ultrasound

- An emerging alternative to radiography for diagnosis. Potential advantages including immediate results, lack of radiation, and less pain.3

Treatment

Conservative

- Conservative treatment is indicated for incomplete fractures and if the ulna has undergone a plastic deformation.

- Typically involves closed reduction and splint immobilization with the elbow flexed at approximately 110° in full supination for 6 weeks.17

Operative12,16,17

- Surgery is often required when the Monteggia fracture of the ulnar shaft is complete.

- Titanium elastic intramedullary nail fixation is recommended for short, oblique fractures.

- Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with plates and screws is recommended for comminuted or long oblique ulna fractures.17

Complications

- Malunion

- Nonunion

- Elbow instability

- Post-traumatic osteoarthritis

- Restricted forearm rotation

Outcomes

- Outcomes in children and adolescents are typically superior to adults. This is likely due to the remodeling ability of small angle deformities, shorter healing time, and the overall stability of Monteggia fractures in the pediatric population.17

Greenstick fracture

- Pediatric forearm fractures are typically described as either complete or greenstick fractures.4

- Greenstick fractures are incomplete, partial thickness fractures in which only the cortex and periosteum are interrupted on one side of the bone but intact on the other side.4,18

- Greenstick fractures are more common among younger children under the age of 10 years, particularly boys, while completed or short oblique fractures are more common in older children.18,19

- The most common mechanism of injury is a fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH), but other possible causes include car accidents, bike accidents, sports injuries, and non-accidental trauma.18

Imaging

- Radiology studies - X-ray

Treatment

Conservative

- Immobilization with casting is indicated for all greenstick fractures and should be performed several days after the initial injury if possible.

- Splinting may be sufficient if there is minimal angulation, appropriate patient compliance and close patient follow-up.

- Closed reduction is also required if the degree of angulation is significant.3,18 See guidelines for acceptable post-reduction alignment in conservative treatment section below.

Complications

- Refracture

- Fracture displacement

Outcomes

- The overall prognosis for greenstick fractures is good, as most patients will heal well without functional or gross changes in the appearance of the injured bone.18

Related Anatomy1-3,8,12,14,20,21

Radius

- At its proximal end, the radius consists of a radial head that articulates with the humerus at the radiocapitellar joint and the ulna at the PRUJ. The radial head is attached to the radial shaft by a narrow radial neck. The shaft of the radius then extends from the neck and expands in diameter as it moves distally. In the distal region, the radial shaft expands to form a rectangular end. The lateral side projects distally as the radial styloid. In the medial surface, there is a concavity, called the ulnar notch, which articulates with the head of ulna to form the DRUJ. The distal surface of the radius has two facets for articulation with the scaphoid and lunate carpal bones. There is also an articulation between the distal radius and the triquetral bone facilitated the triangular fibrocartilage complex. Collectively, these articulations form the radiocarpal joint.

- Ligaments associated with the radius include the radial collateral ligament, annular ligament, and quadrate ligament at its proximal end, and the TFCC at the DRUJ, dorsal and palmar radioulnar ligaments, dorsal radiocarpal ligament, radioscaphocapitate ligament, and long and short radiolunate ligaments at its distal end

- Tendons associated with the radius dorsally include the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL), extensor pollicis longus (EPL), biceps brachii, and brachioradialis tendons.

- In children, both the radius and ulna have proximal and distal physes. The distal physis contributes to 75% of the linear growth of the radius and 80% of the linear growth of the ulna. Forearm fractures in pediatric patients with open physes have a high rate of healing and remodeling.

Ulna

- At its proximal end, the ulna consists of a trochlear notch formed by the olecranon and coronoid process, which articulates with the trochlea of the humerus to form the humeroulnar joint, and with the radius at the radial notch to form the PRUJ. The ulnar shaft is triangular and has three borders (posterior, interosseous, and anterior) and three surfaces (anterior, posterior, and medial). As it moves distally parallel to the radius, the ulnar shaft decreases in width. Its distal end is much smaller than the proximal end and terminates in a rounded head and distal projection called the ulnar styloid process. The head articulates with the ulnar notch of the radius to form the DRUJ.

- Ligaments associated with the ulna include the ulnar collateral ligament, annular ligament, and quadrate ligament at its proximal end, and the TFCC, dorsal and palmar radioulnar ligaments, ulnocarpal ligament, ulnolunate ligament, and ulnotriquetral ligament at its distal end.

- Tendons associated with the ulna include the flexor digitorum profundus, pronator quadratus, flexor carpi ulnaris, extensor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum profundus, supinator, abductor pollicis longus, EPL, and the extensor indicis propius tendons.

- The radius and ulna are attached by the proximal annular ligament, the interosseous membrane along the diaphysis, and distally by the ligaments of the distal radioulnar joint and TFCC. The IOM is an important structure, as its integrity is crucial for fracture stability.

Incidence

- Although fractures of the radius and ulna are the most common fracture type in the pediatric population, epidemiology studies are scarce.3

- One study found that forearm fractures account for 17.8% of all fractures in children and adolescents,22 and the rate of these fractures has been steadily increasing.19

- Both bone forearm fractures account for about 50% all forearm fractures and are significantly more common in male than female patients.23

- Open radius and/or ulna fractures account for 32-80% of all open fractures in the pediatric population.2

- The peak incidence for forearm fractures is 9-12 years, and the greatest risk factor in this age group is include sports activity, particularly football and wrestling.13