Fracture Nomenclature for Triquetrum Fractures

Hand Surgery Resource’s Diagnostic Guides describe fractures by the anatomical name of the fractured bone and then characterize the fracture by the Acronym:

In addition, anatomically named fractures are often also identified by specific eponyms or other special features.

For the Triquetrum Fracture, the historical and specifically named fractures include:

Triquetrum dislocations and fracture-dislocations

By selecting the name (diagnosis), you will be linked to the introduction section of this Diagnostic Guide dedicated to the selected fracture eponym.

Fractures of the carpal bones account for ~6% of fractures overall and up to 18% of all hand fractures. The vast majority (58-89%) occurs in the scaphoid, while fractures of the other 7 carpals are uncommon and only comprise ~1.1% of all fractures. The triquetrum is the most frequently fractured of these bones—the second most overall—with the reported incidence of triquetrum fractures ranging from 3.5-30% of all carpal fractures. Avulsion fractures of the dorsal ridge of the triquetrum are by far the most common fracture pattern, and these injuries typically occur from a fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH) with a volarly flexed and radially deviated wrist. Between 20-50% of triquetrum fractures are associated with other wrist injuries, and the distal ulna and scaphoid are the most commonly fractured bones in these cases. Unlike many other carpal fractures, it appears the majority of triquetrum fractures can be treated conservatively with immobilization alone, while surgery is only reserved for severely displaced fractures and other challenging cases.1-5

Definitions

- A triquetrum fracture is a disruption of the mechanical integrityof the triquetrum.

- A triquetrum fracture produces a discontinuity in the triquetrum contours that can be complete or incomplete.

- A triquetrum fracture is caused by a direct force that exceeds the breaking point of the bone.

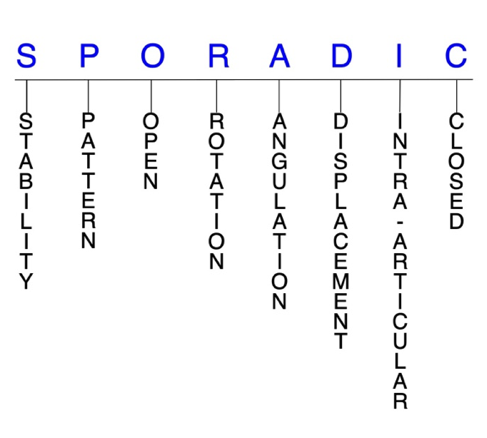

Hand Surgery Resource’s Fracture Description and Characterization Acronym

SPORADIC

S – Stability; P – Pattern; O – Open; R – Rotation; A – Angulation; D – Displacement; I – Intra-articular; C – Closed

S - Stability (stable or unstable)

- Universally accepted definitions of clinical fracture stability is not well defined in the hand surgery literature.6-8

- Stable: fracture fragment pattern is generally nondisplaced or minimally displaced. It does not require reduction, and the fracture fragment’s alignment is maintained with simple splinting. However, most definitions define a stable fracture as one that will maintain anatomical alignment after a simple closed reduction and splinting. Some authors add that stable fractures remain aligned, even when adjacent joints are put to a partial range of motion (ROM).

- Unstable: will not remain anatomically or nearly anatomically aligned after a successful closed reduction and simple splinting. Typically unstable triquetrum fractures have significant deformity with comminution, displacement, angulation, and/or shortening.

P - Pattern

- Triquetrum body: sagittal, oblique, transverse, and/or comminuted

- Sagittal fractures are typically associated with crush injuries or axial dislocations, while transverse fractures are associated with perilunate injuries and comminuted fractures are from high-energy trauma.2

- Isolated transverse fractures are very rare and must be differentiated from avulsion fractures.9

- Triquetrum dorsal ridge (posterior tubercle)

- Acts as the divide between the dorsal and volar cortices.

- Triquetrum fractures can be classified by their anatomic location into one of the following 3 types:

- Type 1: dorsal cortex fractures

- Most common fracture pattern, especially avulsion fractures of the dorsal ridge, which account for >90% of all triquetrum fractures.10

- The 2 likely mechanisms of injury are compression fractures—caused by a chisel action of the ulnar styloid process upon the dorsum of the triquetrum, resulting from a FOOSH with the wrist in dorsiflexion and ulnar deviation—and avulsion fractures, which commonly occurs in falls with a volarly flexed wrist and radially deviated hand.3

- Less common and usually associated with carpal dislocation or other carpal fractures.

- Typically result from excessive force during a FOOSH with greater dorsiflexion and more ulnar deviation, under the impingement of ulnar styloid process against the triquetrum.3

- Intra-articular fractures at the distal end of the triquetrum body can also occur from an impaction of a deviated pisiform that produce shear forces on the surface of the triquetrum. These extremely rare injuries are sometimes referred to as osteochondral fractures, but “intra-articular fractures” is preferred.5

- Type 3: volar cortex fractures

- Extremely rare fracture pattern.

- Injury mechanism is considered to be a sheared force of pisiform on the volar, distal, and ulnar surface of triquetrum.3

O - Open

- Open: a wound connects the external environment to the fracture site. The wound provides a pathway for bacteria to reach and infect the fracture site. As a result, there is always a risk for chronic osteomyelitis. Therefore, open fractures of the triquetrum require antibiotics with surgical irrigation and wound debridement.6,11,12

- Open fractures of the triquetrum require surgical exploration to determine if articular surfaces are involved. After irrigation and debridement, these wounds are sometimes left open and further treatment is typically delayed until the wound shows no sign of infection.13,14

R - Rotation

- Triquetrum fracture deformity can be caused by rotation of the distal fragment on the proximal fragment.

- Degree of malrotation of the fracture fragments can be used to describe the fracture deformity.

A - Angulation (fracture fragments in relationship to one another)

- Angulation is measured in degrees after identifying the direction of the apex of the angulation.

- Straight: no angulatory deformity

- Angulated: bent at the fracture site

D - Displacement (Contour)

- Displaced: disrupted cortical contours

- Nondisplaced: fracture line defining one or several fracture fragments; however, the external cortical contours are not significantly disrupted

I - Intra-articular involvement

- Fractures that enter a joint with one or more of their fracture lines.

- Triquetrum fractures can have fragment involvement at any of its intercarpal joint articulations.

- If a fracture line enters a joint but does not displace the articular surface of the joint, then it is unlikely that this fracture will predispose to posttraumatic osteoarthritis. If the articular surface is separated or there is a step-off in the articular surface, then the congruity of the joint will be compromised and the risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis increases significantly.

- Intra-articular fractures at the distal end of the triquetrum body have been documented but are extremely rare.5

C - Closed

- Closed: no associated wounds; the external environment has no connection to the fracture site or any of the fracture fragments.6-8

Triquetrum fractures: named fractures, fractures with eponyms and other special fractures

Triquetrum dislocations and fracture-dislocations

- Although fractures of the triquetrum are fairly common, dislocations are extremely rare due to the very strong ligamentous support between its surfaces and the surrounding carpal bones.15

- Dorsal triquetral dislocations are typically associated with other hand injuries, while volar dislocations are more likely to be isolated injuries.15

- Possible mechanisms of injury include wrist flexion with ulnar deviation and supination, hyperextension, and a direct blow to the hand.15,16

- Triquetrum dislocations can also occur in the sequence of a trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocation, in which the link between the lunate and triquetrum is broken.17

Imaging

- Routine radiographs

- Triquetrum dislocations are often missed on the initial diagnosis when evaluated solely with routine radiographic views, as the bone is difficult to visualize: the pisiform obscures the triquetrum on the posteroanterior (PA) view and the scaphoid does so on the lateral view.

- The oblique view is considered most effective for visualizing triquetral dislocations.18

- Some authors recommend a digital volume tomography or CT scan if a fracture is suspected or there is any sign of carpal misalignment on plain radiographs.15

- Delays in diagnosis and treatment may lead to irreversible damage to bone and cartilage, and surgical intervention may become necessary, which is why high clinical suspicion is needed when evaluating these wrist injuries.15

Treatment

- Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning (CRPP)

- Often not feasible for acute dislocations, but if it is achieved, K-wires should be used to facilitate healing of the lunotriquetral ligament and prevent redislocation.15

- Open reduction and fixation (ORIF)

- The preferred treatment for most triquetral dislocations.15

- Fixation may be achieved using either K-wires or Herbert bone screws, and a volar approach appears to be more suitable for volar dislocations.15,18

- When applicable, direct repair of torn ligaments should also be performed.15

- Triquetrum excision

- May be required in some extreme cases.16

Complications

- Infection

- Carpal instability

Outcomes

- In general, when triquetral dislocations are diagnosed and treated promptly, good functional outcomes have been reported. Studies have shown that in these cases, most patients experienced little or no pain and only slightly restricted wrist ROM and grip strength at follow-up.15

- Other studies have reported cases successfully treated with CRPP, ORIF, and triquetrum excision.16

Related Anatomy

- The triquetrum is a roughly pyramidal-shaped bone located on the medial side of the proximal carpal row that consists of a body and a transverse, dorsal ridge—or posterior tubercle—which divides the volar and dorsal cortices. It articulates distally with the hamate, volarly with the pisiform, radially with the lunate, and proximally with the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC), and does not actually attach to the ulna.

- Along with the scaphoid and lunate, the triquetrum also forms the distal articular surface of the radiocarpal joint.5,19

- Despite being the second most common carpal fracture, the triquetrum is well protected proximally by the TFCC and distally by the hamate.20

- Ligamentous attachments of the triquetrum include the volar scaphotriquetral, volar radiolunatotriquetral, ulnotriquetral, lunotriquetral, and ulnar collateral ligaments. The volar radiolunatotriquetral ligament, which originates from the ulnar side of the radioscaphocapitate ligament and inserts into the lunate and triquetrum, is one of the strongest of all carpal ligaments.3,5

- The triquetrum does not have any tendinous attachments.

Incidence and Related injuries/conditions

- Fractures of the carpal bones have been found to account for 8-18% of all hand fractures21,22and ~6% of fractures overall.23

- Fractures of the proximal carpals are more common than the distal carpals, and the most commonly fractured carpal bone is the scaphoid, which represents 58-89% of all carpal fractures.21,22,24,25

- Fractures of the other 7 carpals are very rare and only account for ~1.1% of all fractures. The triquetrum ranks highest of these bones, while fractures of the remaining carpals are even less common and vary in incidence.10,26,27

- According to the literature, the triquetrum is the second most frequently fractured carpal bone, with a reported incidence ranging from as low as 3.5%10to as high as 30%28of all carpal fractures.

- Approximately 12-25% of all triquetrum fractures are associated with perilunate fracture-dislocations.29

- In one series, the incidence of triquetrum fractures (27.4%) was actually found to be higher than that of scaphoid fractures (25.1%), but this may have been due to selection bias.3

- Triquetrum fractures have been reported as radiographically occult in up to 80% of cases and are associated with other wrist injuries in 20-50% of cases.19

- When they do occur concomitantly with other fractures, the distal radius—with or without the distal ulna—and scaphoid are most likely to be involved.4