Fracture Nomenclature for Lunate Fracture

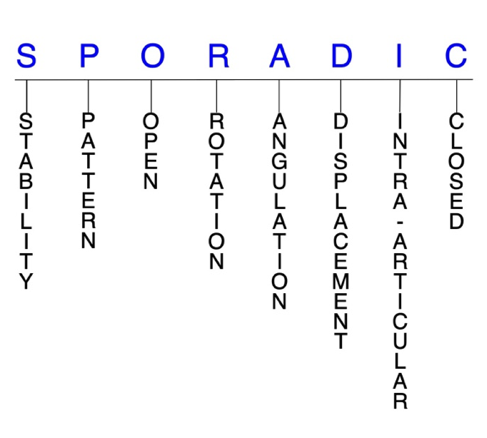

Hand Surgery Resource’s Diagnostic Guides describe fractures by the anatomical name of the fractured bone and then characterize the fracture by the Acronym:

In addition, anatomically named fractures are often also identified by specific eponyms or other special features.

For the Lunate Fracture, the historical and specifically named fractures include:

Perilunate dislocation and fracture-dislocation

Lunate dislocation and fracture-dislocation

By selecting the name (diagnosis), you will be linked to the introduction section of this Diagnostic Guide dedicated to the selected fracture eponym.

Fractures of the carpal bones account for ~6% of all fractures and up to 18% of all hand fractures. The vast majority (58-89%) occurs in the scaphoid, while fractures of the other 7 carpals are rare, accounting for ~1.1% of all fractures. The incidence of lunate fractures is estimated to be from 0.5-6.5% of all carpal fractures. Rarely seen in isolation, lunate fractures are usually concomitant with other carpal injuries—especially of the scaphoid—and occur in conjunction with a perilunate fracture-dislocation in 5-7% of wrist injuries. Lunate fractures are often associated with avascular necrosis(AVN) of the lunate. The most common mechanism of injury is a fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH) with a dorsiflexed, ulnarly-deviated wrist that drives the capitate down into the lunate. Lunate fractures are difficult to treat, and there is some controversy and a lack of consensus regarding the management of several injury patterns, but it appears that surgery is frequently required and associated with better outcomes than conservative strategies.1-5

Definitions

- A lunate fracture is a disruption of the mechanical integrityof the lunate.

- A lunate fracture produces a discontinuity in the lunate contours that can be complete or incomplete.

- A lunate fracture is caused by a direct force that exceeds the breaking point of the bone.

Hand Surgery Resource’s Fracture Description and Characterization Acronym

SPORADIC

S – Stability; P – Pattern; O – Open; R – Rotation; A – Angulation; D – Displacement; I – Intra-articular; C – Closed

S - Stability (stable or unstable)

- Universally accepted definitions of clinical fracture stability is not well defined in the hand surgery literature.6-8

- Stable: fracture fragment pattern is generally nondisplaced or minimally displaced. It does not require reduction, and the fracture fragment’s alignment is maintained with simple splinting. However, most definitions define a stable fracture as one that will maintain anatomical alignment after a simple closed reduction and splinting. Some authors add that stable fractures remain aligned, even when adjacent joints are put to a partial range of motion (ROM).

- Unstable: will notremain anatomically or nearly anatomically aligned after a successful closed reduction and simple splinting. Typically unstable lunate fractures have significant deformity with comminution, displacement, angulation, and/or shortening.

- Isolated dorsal lunate dislocations can be unstable, even if there is no associated lunate fracture.9

P - Pattern

- Lunate dorsal pole (lip): may result from scapholunate or lunotriquetral interosseous or dorsal radiocarpal ligament avulsion; impingement of the dorsal pole between the radius and capitate during extreme wrist dorsiflexion can also produce an impaction fracture1

- An avulsion fracture may occur because the dorsal pole serves as the attachment point of several major ligaments.10

- Lunate volar pole (lip): may result from avulsion of the long and/or short radiolunate ligaments1

- An avulsion fracture may occur because the volar pole also serves as the attachment point of several major ligaments10

- Lunate body: sagittal, coronal, transverse, and/or comminuted2-4

- Often occur secondary to axial loading of the lunate between the capitate head and lunate fossa1

- One classification system uses the following 5 groups to categorize lunate fractures:

- Group I: volar pole fractures

- Group II: chip fractures

- Group III: dorsal pole fractures

- Group IV: sagittal fractures through the body

- Group V: transverse fractures through the body4,11

- Osteochondral and transarticular body fractures of the lunate are also possible.2

O - Open

- Open: a wound connects the external environment to the fracture site. The wound provides a pathway for bacteria to reach and infect the fracture site. As a result, there is always a risk for chronic osteomyelitis. Therefore, open fractures of the lunate require antibiotics with surgical irrigation and wound debridement.6,12,13

- ~10% of perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations are open injuries, and 26% are associated with polytrauma.14

- High-energy injuries that involve open perilunate dislocations and a devascularized lunate have been found to be capable of healing with acceptable wrist function and revascularization.15

- Under the Herzberg classification system, perilunate dislocations are considered stage I injuries, and lunate dislocations are stage II. Lunate dislocations are further classified as stage IIA when the lunate has subluxated out of its fossa but has rotated <90° and as stage IIB when lunate rotation is >90°.18,19

- Open fractures of the lunate may require surgical exploration to determine if articular surfaces are involved. After irrigation and debridement, these wounds are generally closed if the joint and fracture contamination has been elliminated. When there is doubrt the would is left open and secondary I&D's are done and the wound is closed when htere is no sign of infection.16,17

R - Rotation

- Lunate fracture deformity can be caused by rotation of the distal fragment on the proximal fragment.

- Degree of malrotation of the fracture fragments can be used to describe the fracture deformity.

- If an offending force is sufficient enough—such as from a FOOSH with extreme dorsiflexion and ulnar deviation—the lunate will dislocate and rotate volarly, which is the final stage of a perilunate dislocation.20

- In lunate dislocations, the spilled teacup sign seen on the lateral radiograph is created by proximal rotation of the lunate about its attached volar ligaments. If the lunate rotates >90°, it is seen as a triangular shape rather than its normal quadrilateral shape and appears absent from its normal location on an anteroposterior (AP) radiographic view.18,21

A - Angulation (fracture fragments in relationship to one another)

- Angulation is measured in degrees after identifying the direction of the apex of the angulation.

- Straight: no angulatory deformity

- Angulated: bent at the fracture site

- In this small carpal bone signficant angulation is rare.

D - Displacement (Contour)

- Displaced: disrupted cortical contours

- Nondisplaced: fracture line defining one or several fracture fragments; however, the external cortical contours are not significantly disrupted

- In lunate dislocations, the lunate becomes displaced as it rotates volarly, while the rest of the carpal bones remain in normal anatomic position in relation to the radius.21

- Radiocarpal instability is usually displaced in a dorsoradial direction, while midcarpal instability is usually displaced in a volar direction.5

- Volar or dorsal pole fractures may be displaced, and the hallmark sign is translation of the capitate in the respective direction of the affected pole.2

I - Intra-articular involvement

- Fractures that enter a joint with one or more of their fracture lines.

- Lunate fractures can have fragment involvement with the radius or any of its intercarpal joint articulations.

- If a fracture line enters a joint but does not displace the articular surface of the joint, then it is unlikely that this fracture will predispose to posttraumatic osteoarthritis. If the articular surface is significantly separated, or there is a step-off in the articular surface, then the congruity of the joint will be compromised and the risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis increases significantly.

- Transverse translunate fracture-dislocations are intra-articular fractures of the lunate.22

C - Closed

- Closed: no associated wounds; the external environment has no connection to the fracture site or any of the fracture fragments.6-8

Lunate fractures: named fractures, fractures with eponyms, and other special fractures

Perilunate dislocation and fracture-dislocation

- Dislocations of the lunate are typically divided into perilunate and lunate varieties.23

- Perilunate dislocations and perilunate fracture-dislocations comprise a spectrum of challenging injury patterns that typically occur after a fall from a height, motor vehicle accident, or injury during sporting activities.18

- The majority of perilunate dislocations are dorsal, with only 3% being volar, and these injuries involve a dorsal dislocation of the capitate with respect to the lunate, while the lunate remains in its normal position in the lunate fossa.18,22

- Perilunate dislocation is the most common pattern of carpal dislocation.9

- These are devastating high-energy injuries that are commonly seen after a FOOSH in extremes of dorsiflexion and ulnar deviation.

- The arc that the dislocating torque follows has been described: it begins with disruption of the scapholunate ligament or fracture of the scaphoid followed by lunatocapitate disruption and then by disruption of the lunatotriquetral ligament. Eventually, if the force is sufficient, the lunate dislocates and rotates volarly, which is the final stage of perilunate dislocation.20

- Perilunate fracture-dislocations are frequently seen in the literature and combine ligament ruptures, bone avulsions, and fractures in a variety of clinical forms. The most common is the transscaphoid perilunate dislocation, while variants of this pattern include those associated with fractures of the capitate, triquetrum, lunate, distal radius, radial styloid, and ulnar styloid.3,24

- Lunate fractures occur in conjunction with a perilunate fracture-dislocation in 5-7% of wrist injuries, and the latter usually occur among men aged 20-30 years after a fall from a significant height, a motor vehicle accident or motorcycle accident involving high kinetic energy.25,26

- ~10% of perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations are open injuries, and 26% are associated with polytrauma.14

- Perilunate injuries are considered to be a greater or lesser arc depending on the presence of associated carpal fractures or ligamentous disruptions.5

- A greater arc injury is one with an associated fracture of one or more bones around the lunate, while a lesser arc injury is associated with pure ligamentous disruption around the lunate.20

- Similarly, translunate fracture-dislocations are often part of a more significant carpal injury, and the translunate arc concept describes lunate fractures as a variant of the lesser and greater arc injuries.5

- Translunate arc describes rare, usually high-energy injuries in which a perilunate dislocation occurs with a lunate fracture, which further destabilizes the carpus.18

- The Mayfield et al. classification system for perilunate injuries and carpal instability is commonly used to better inform treatment decisions:

- Stage I: scapholunate dissociation, with failure of the scapholunate or radioscaphocapitate ligament

- Stage II: perilunate dislocation, in which the capitolunate joint is disrupted; ~60% are associated with scaphoid fractures

- Stage III: midcarpal dislocation, which includes disruption of the triquetrolunate interosseous ligament or triquetral fracture; neither the capitate or the lunate is aligned with the distal radius

- Stage IV: lunate dislocation from the lunate fossa, which usually occurs in a volar direction and involves a failure of the radiocarpal ligament27

- Stage V: complete volar lunate dislocation with a carpal fracture. This tytpe described by Cooney et al.28 is the most severe type of perilunate fracture-dislocation

- Another classification system by Herzberg et al. expands on the Mayfield system to include rotational details:

- Stage I: Mayfield stages I-III

- Stage II: Mayfield stage IV

- Stage IIA: Mayfield stage IV with lunate dislocated volarly and rotated <90°

- Stage IIB: Mayfield stage IV with lunate dislocated volarly and rotated >90°19

Imaging

- Diagnosis is difficult, as clinical symptoms are nonspecific on account of the lunate having the largest cartilage-covered area of all the carpals.

- It has been found that up to 25% of perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations are missed on clinical and radiographic examination. Failing to properly diagnose these injuries can lead to a delay in management and unfavorable outcomes.3,18

- Standard wrist posteroanterior (PA) and lateral radiographs are most useful.

- The PA view should be scrutinized for uneven gapping in the carpal bones, and the 3 smooth carpal arcs of Gilula should be free of discontinuity.

- These injuries are often seen on PA radiographs as a loss of carpal height with overlapping of the carpal bones, particularly the capitate and lunate.

- On lateral radiographs, the hallmark sign is a loss of colinearity of the radius, lunate, capitate and metacarpals.18

- A CT scan may be needed if there is any doubt and in order to avoid a delay in diagnosis.

- Can determine the type of fracture(s), the amount of displacement, degree of comminution, if there are any associated ligament injuries, and to identify an occult fracture.18,22

- Particularly helpful for detecting occult greater arc injuries.20

- MRI without contrast is effective for identifying intercarpal ligamentous ruptures and occult fractures or bone contussions. MRIs are therefore more useful for lesser arc injuries.18,20

Treatment

- Perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations should be considered emergencies that require prompt intervention to increase the chances of a positive outcome.20

- These injuries were historically managed with closed reduction and casting, and some clinicians continue to treat these injuries conservatively today, but these methods have been found to result in unsatisfactory outcomes. This is why the current standard is closed reduction followed by open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) that includes ligamentous and bony repair.18,20

- The first step of treatment is immediate, gentle, closed reduction, which is needed to decrease pressures on critical neurovascular structures and cartilage. Reduction is performed with the elbow flexed to 90° and the hand placed into finger traps.

- Stable closed reduction is typically achieved, with reported maintenance of reduction in >90% of cases, and significant muscle relaxation improves the chances for a successful closed reduction.

- Open reduction, ligament and bone repair, and supplemental fixation are typically performed within 3-5 days afterwards as swelling subsides.

- The surgical maxim for greater arc injuries is fixation of the bony involvement before soft-tissue repair. Scaphoid fractures are typically fixed using cannulated headless screw systems, while comminuted fractures can be treated with K-wire fixation and autologous bone grafting from the distal radius.

- Fixation is then followed by a period of cast immobilization.18

- For perilunate fracture-dislocations with a transverse lunate fracture, a dorsal approach is typically used to reduce the intra-articular fracture of the lunate and reduce the scapholunate and lunotriquetral diastasis by ligament reattachment and temporary K-wire pinning.22

- Carpal tunnel syndrome has been frequently identified in delayed presentations of volar lunate dislocations, and carpal tunnel release is frequently needed in these cases if any median nerve symptoms are present.9

- Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning (CRPP) may also be used for perilunate dislocations, while arthroscopy is another surgical option for perilunate fracture-dislocations.18,22

Complications

- Posttraumatic osteoarthritis

- Median nerve dysfunction

- Complex regional pain syndrome

- Hand or wrist weakness

- Tendon ruptures/dysfunction

- Residual carpal instability

- Infection

- Nonunion

- Malunion

- Avascular necrosis (AVN) or transient ischemia of the lunate

Outcomes

- Perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations are severe injuries with a poor prognosis for return to full previous function.

- Open injuries, those with delayed treatment, those with osteochondral fractures of the capitate head, and the presence of persistent carpal malalignment all imply poorer outcomes, while outcomes are improved by early, accurate reduction and stable internal fixation.18

- One study of 28 perilunate dislocations with scaphoid fractures treated with early open reduction, ligamentous repair, and cast immobilization led to satisfactory results.22

- In another study of 32 patients with a perilunate dislocation or fracture-dislocation treated with closed reduction and immobilization, more than half failed to maintain reduction.29

- A comparison trial of 28 patients with perilunate dislocation or fracture-dislocation found that 12 of 20 wrists managed with ORIF had good or excellent results, while the 8 treated with closed reduction and casting had fair or poor outcomes.30

- Reports of acceptable results with ORIF have also been published when treatment was delayed for up to 6 months.31,32

Lunate dislocation and fracture-dislocation

- Although the two entities should be viewed and addressed separately, it is generally agreed that lunate and perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations are different stages of the same injury pattern.18,23,33

- To differentiate, the lunate is displaced and rotated volarly in lunate dislocations, while the rest of the carpal bones are in a normal anatomic position in relation to the radius. In perilunate dislocations, the radiolunate articulation is preserved and the rest of the carpus is displaced dorsally.18

- Based on the Herzberg classification system, all perilunate injuries are considered stage I, while all lunate injuries are stage II.19

- Dislocation of the lunate is usually in the volar direction, while dorsal, isolated dislocations of the lunate are extremely rare and usually associated with concomitant fractures of other carpal bones or the distal radius.9

- Volar lunate dislocation can be classified as Herzberg stage II and are considered the final stage of the perilunate fracture-dislocation spectrum.33

- However, a complete volar lunate dislocation combined with a carpal fracture is the most severe type of perilunate fracture-dislocation, which is considered Mayfield stage V.33

- Lunate dislocations are commonly associated with fracture of one or more other carpal bones, and as with perilunate dislocations, the scaphoid is most commonly involved.9,34

- In these injuries, the capitate has reduced from its dorsally dislocated position to become colinear with the radius, dislocating the lunate into the carpal tunnel.18

Imaging

- In lunate dislocations, an anteroposterior (AP) radiographic view shows the lunate as absent from its normal location with a large gap in this region. If the lunate rotates >90°, it is seen as a triangular shape rather than its normal quadrilateral shape.

- On the lateral radiograph, the lunate appears displaced volarly and is usually rotated in lunate dislocations. A search for the head of the capitate reveals that it does not articulate as it should with the lunate.21

- A CT scan or MRI may be needed in some cases that are difficult to diagnose.

Treatment

- Treatment for lunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations is somewhat controversial, but most agree that surgery is always necessary and that closed reduction is only appropriate as an initial treatment for Herzberg stage IIA injuries—volar lunate dislocations rotated <90°. Prompt surgical intervention appears to be necessary for all stage IIB injuries, open injuries, and whenever adequate reduction is not possible or difficult to maintain.5,18,34

- Most experts also agree that lunate fracture-dislocations are complex injuries that require stabilization of the lunate and of any associated fractures and/or ligament injuries.5

- Closed reduction for stage IIA lunate dislocations begins with wrist flexion to release tension on the volar ligaments, and is followed with dorsally directed pressure placed on the lunate to reduce it into the lunate fossa.

- After reduction, the wrist is extended, traction is exerted, and the wrist is flexed, all while maintaining a volar buttress with a digit to the lunate. This maneuver should relocate the capitate back onto the recently reduced lunate stabilized by volar pressure.

- Once this is completed, the injured extremity is placed in neutral rotation into a sugar tong splint to allow elevation and full ROM of the fingers. If an acceptable, stable reduction is achieved, surgery is typically performed 3-4 days later when swelling has improved.18

- Internal fixation with K-wires, external fixation with K-wires, arthroscopy, and open surgery have all been discussed in the literature as surgical options for these injuries, but research on outcomes and optimal management strategies is scarce.34

- Lunate fracture-dislocations may also require a neutralization device such as a bridging plate to prevent loss of fixation and collapse of the carpus.5

- The rare isolated, dorsal lunate dislocation may also respond well to closed reduction and K-wire fixation alone, followed by a short period of cast immobilization.9

Complications

- Posttraumatic osteoarthritis

- Median nerve dysfunction

- Complex regional pain syndrome

- Hand or wrist weakness

- Tendon ruptures/dysfunction

- Residual carpal instability

- Infection

- Nonunion

- Malunion

- Transient ischemia of the lunate

Outcomes

- In one study, lunate fracture-dislocations were associated with a poor prognosis and high risk of complications: of the 14 patients with this injury, 8 had nonunion, developed avascular necrosis, or required an early or late salvage procedure.5

Related Anatomy

- The lunate is located in the center of the proximal row of the carpus. It consists of a body and a volar and dorsal pole, which are the attachment points of several major ligaments and help give the bone the crescent shape it’s named for. Its distal aspect is concave and articulates with the capitate, while proximally it articulates with the lunate facet of the distal radius, laterally with the scaphoid, and medially with the triquetrum. In some patients, the lunate also articulates with the hamate distally/medially by a long, narrow facet.10,35

- Along with the scaphoid and triquetrum, the lunate also forms the distal articular surface of the radiocarpal joint.

- Since it resides within the lunate fossa, a protected concavity of the distal radius, the lunate can be considered a “carpal keystone.” It is also integral in the flexion/extension arc and the radial/ulnar deviation arc at both the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints.35

- Ligamentous attachments of the lunate include the scapholunate, lunotriquetral, lunatocapitate, radiolunotriquetral, radioscapholunate, ulnolunate, and radiolunate ligaments.9

- The ulnocarpal ligamentous complex consists of the ulnolunate, ulnotriquetral, and ulnocapitate ligaments. It merges firmly with the volar radioulnar ligament and plays an important role in maintaining the stability of the distal radioulnar joint through the triangular fibrocartilage complex. Impairment of the ulnolunate ligament can therefore cause chronic ulnar wrist pain.10

- The lunate does not have any tendinous attachments.

- Of all the carpal bones, the lunate bone has proportionally the largest cartilage-covered area, and its proximal portion is made up almost completely of articular cartilage with no soft tissue attachment and a poor blood supply.35

Incidence and Related injuries/conditions

- Fractures of the carpal bones have been found to account for 8-18% of all hand fractures36,37and ~6% of fractures overall.38

- Fractures of the proximal carpals are more common than the distal carpals, and the most commonly fractured carpal bone is the scaphoid, which represents 58-89% of all carpal fractures.36,37,39,40

- Fractures of the other 7 carpals are very rare and only account for ~1.1% of all fractures. The triquetrum ranks highest of these bones, while fractures of the remaining carpals are even less common and vary in incidence.41-43

- The incidence of lunate fractures is not clearly defined and has been reported to range from 0.5-6.5% of all carpal fractures.11,44. There is some controversy regarding this figure, and it’s been suggested that the higher end of the range may include some overestimations, as some investigators likely included Kienböck’s disease, dorsal triquetral fractures, and/or bipartite lunates in their diagnoses of lunate fractures.1,2

- Lunate fractures occur in conjunction with a perilunate fracture-dislocation in 5-7% of wrist injuries

Work-up Options

- Routine X-rays

- A normal lateral radiograph will show the capitate, lunate, and distal radius collinear with the wrist in a neutral position.35

- Standard AP, lateral, and oblique radiographs frequently fail to visualize or underestimate the size or displacement of lunate fracture fragments.

- On the AP view, any widening of the scapholunate space—scapholunate dissociation—is a clue to a possible occult lunate fracture.1,2

- The hallmark of a displaced volar or dorsal pole fracture of the lunate is translation of the capitate in the respective direction of the affected pole.2

- When assessing the position of the carpal bones on plain radiographs, Gilula’s lines are a useful point to start from.9

- CT scan

- Typically recommended when plain radiographs fail to provide a clear diagnosis and clinical suspicion remains.

- Will help to provide a greater definition of the fracture configuration and the degree of displacement, and to identify fractures that may be obscured by overlapping carpals on plain radiographs.2

- Particularly helpful for identifying lunate body fractures.1

- MRI

- Considered the best imaging modality for diagnosing lunate fractures, as it clearly visualizes the carpus and has the added ability to detect early vascular compromise within these bones, so it may also identify chondral and ligamentous injuries as well.5

- Also desirable when radiation needs to be avoided, as in children and pregnant women, and asensitive tool in the follow-up of avascular necrosis and fracture healing.18

- Bone scan