Fracture Nomenclature for Capitate Fracture

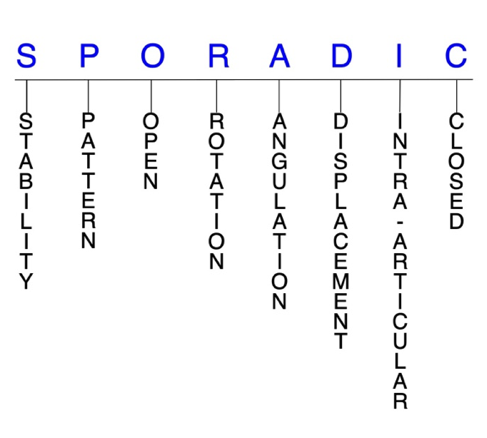

Hand Surgery Resource’s Diagnostic Guides describe fractures by the anatomical name of the fractured bone and then characterize the fracture by the Acronym:

In addition, anatomically named fractures are often also identified by specific eponyms or other special features.

For the Capitate Fracture, the historical and specifically named fractures include:

Scaphocapitate fracture syndrome

Capitate dislocation and fracture-dislocation

By selecting the name (diagnosis), you will be linked to the introduction section of this Diagnostic Guide dedicated to the selected fracture eponym.

Fractures of the carpal bones account for ~6% of fractures overall and up to 18% of all hand fractures. The majority (58-89%) occurs in the scaphoid, while fractures of the other 7 carpals are uncommon and comprise ~1.1% of all fractures. The capitate is the largest and most protected of the carpals; consequently, capitate fractures account for 1-2% of carpal fractures; however, their true incidence is unknown because accurate diagnoses are often missed. Although rare, capitate fractures can be serious injuries that require careful detection and an appropriate management strategy to reduce the risk for complications. Nondisplaced capitate fractures—especially those that are isolated—can often be effectively treated with closed reduction and immobilization, while surgery is typically needed for displaced and/or comminuted fractures, or when conservative methods fail.1-7

Definitions

- A capitate fracture is a disruption of the mechanical integrity of the capitate.

- A capitate fracture produces a discontinuity in the capitate contours that can be complete or incomplete.

- A capitate fracture is caused by a direct force that exceeds the breaking point of the bone.

Hand Surgery Resource’s Fracture Description and Characterization Acronym

SPORADIC

S – Stability; P – Pattern; O – Open; R – Rotation; A – Angulation; D – Displacement; I – Intra-articular; C – Closed

S - Stability (stable or unstable)

- Universally accepted definitions of clinical fracture stability is not well defined in the hand surgery literature.8-10

- Stable: fracture fragment pattern is generally nondisplaced or minimally displaced. It does not require reduction, and the fracture fragment’s alignment is maintained with simple splinting. However, most definitions define a stable fracture as one that will maintain anatomical alignment after a simple closed reduction and splinting. Some authors add that stable fractures remain aligned, even when adjacent joints are put to a partial range of motion (ROM).

- Unstable: will not remain anatomically or nearly anatomically aligned after a successful closed reduction and simple splinting. Typically unstable capitate fractures have significant deformity with comminution, displacement, angulation, and/or shortening.

- The intercarpal ligaments offer a great deal of extrinsic stability to the capitate, while its cuboidal shape provides additional strength to the bone. This is why the majority of capitate fractures are stable and nondisplaced.3,11

P - Pattern

- Capitate head: this fracture pattern appears to be rare

- Capitate neck (waist): the most common site of fracture in the capitate, these injuries are usually transverse in configuration5

- Capitate body: may be stellate comminuted, oblique, or transverse, but transverse is most common; these fractures can result from a direct blow that causes multiple carpal fractures or as part of an incomplete or self-reduced perilunate injury1,12

- Other possible capitate fracture patterns include verticofrontal, parasagittal, avulsion tip, or shear depression fractures.2,12

- The mechanism of injury often dictates the fracture pattern.2

- Different mechanisms of injury for capitate fractures have been proposed, and the matter is still debated. In many cases, the exact mechanism is difficult to determine.

- The most common mechanism identified has been a FOOSH with an extended wrist (77%), which applies a dorsiflexion force to the wrist in neutral, ulnar, or radial deviation.

- A fall onto the dorsum of the hand, which applies a flexion force to the wrist, appears to be the second mechanism in terms of frequency (15.4%).

- A direct blow or an axial trauma, transmitted through the heads of the index and long metacarpals in a clenched fist and flexed wrist, are also possible causes. Stress fractures and pathological fractures have been described as well.6,7,13

- Ligaments anchor the body of the capitate to the trapezoid, hamate, and base of the metacarpals, which leaves the head and the neck vulnerable to rapid high-energy impact, bending, axial, shear, and torsion forces. Adjacent carpals or the borders of the radius may impinge the head or neck, further accentuating these forces.5

O - Open

- Open: a wound connects the external environment to the fracture site. The wound provides a pathway for bacteria to reach and infect the fracture site. As a result, there is always a risk for chronic osteomyelitis. Therefore, open fractures of the capitate require antibiotics with surgical irrigation and wound debridement.8,14,15

- Open fractures of the capitate may require surgical exploration to determine if articular surfaces are involved. After irrigation and debridement, these wounds are generally left open and further treatment is typically delayed until the wound shows no sign of infection.16,17

R - Rotation

- Capitate fracture deformity can be caused by rotation of the distal fragment on the proximal fragment.

- Degree of malrotation of the fracture fragments can be used to describe the fracture deformity.

- Scaphocapitate fracture syndrome consists of concomitant fractures of the scaphoid and capitate with a rotation of 90-180° of the proximal fragment of the capitate.18

- Rotatory dislocation of the capitate can be considered a combination of a dorsal carpometacarpal (CMC) joint dislocation of the long metacarpal and a midcarpal dislocation at the luno-capitate articulation.19

A - Angulation (fracture fragments in relationship to one another)

- Angulation is measured in degrees after identifying the direction of the apex of the angulation.

- Straight: no angulatory deformity

- Angulated: bent at the fracture site

- Example: in displaced oblique capitate neck fractures, the proximal fragment may be ulnarly angulated and pronated in relation to the distal fragment5

- Due to its anatomic position and inherent stability, isolated capitate fractures are often nondisplaced; however, in perilunate injuries, proximal capitate fragments can be displaced and rotated as much as 180°.5,11,20

- Since the principal intraosseous blood supply of the capitate flows retrograde from the body to the head, displaced fractures jeopardize the viability of the proximal pole.5

D - Displacement (Contour)

- Displaced: disrupted cortical contours

- Nondisplaced: fracture line defining one or several fracture fragments; however, the external cortical contours are not significantly disrupted

I - Intra-articular involvement

- Fractures that enter a joint with one or more of their fracture lines.

- Capitate fractures can have fragment involvement with any of its CMC or intercarpal joint articulations.

- If a fracture line enters a joint but does not displace the articular surface of the joint, then it is unlikely that this fracture will predispose to posttraumatic osteoarthritis. If the articular surface is separated or there is a step-off in the articular surface, then the congruity of the joint will be compromised and the risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis increases significantly.

- The implications of displaced intra-articular capitate fractures are the same as fractures of other carpal bones in terms of carpal mechanics.13

- Dorsal distal articular margin capitate fractures occur as part of long CMC joint fracture-dislocations, where the mechanism of injury is axial loading combined with a flexion moment applied to the long metacarpal.1

C - Closed

- Closed: no associated wounds; the external environment has no connection to the fracture site or any of the fracture fragments.8-10

Capitate fractures: named fractures, fractures with eponyms and other special fractures

Scaphocapitate fracture syndrome

- Rare but complex injury that is a manifestation of the perilunate injury pattern.1,21

- These injuries most commonly occur in young men between ages 20-30.22

- The most recognized mechanism of injury is a volar-applied force to a hyperextended wrist, such as from a fall from a height or vehicular accident.22

- This wrist hyperextension results in a scaphoid fracture and, with further extension, the capitate impacts on the dorsal lip of the radius. This produces a transverse capitate body fracture, in which its proximal fragment rotates 90-180° in the sagittal plane as the hand returns to a neutral position. The articular cartilage of the capitate head then faces distally in opposition to the fracture surface of the distal capitate fragment.1

- Can be either isolated or associated with a perilunate dislocation, but a substantial force is usually required to cause a dislocation.22

- In one study, scaphocapitate fractures were classified into 6 patterns based on fragment geometry and displacement:

- Type I: transverse fracture of the scaphoid and capitate without dislocation

- Type II: inverted proximal fragment of capitate that remains in articulation with the lunate

- Type III: dorsal perilunate dislocation

- Type IV: volar perilunate dislocation of the carpus and proximal fragment of capitate

- Type V: isolated volar dislocation of the proximal fragment of capitate

- Type VI: isolated dorsal dislocation of the proximal fragment of capitate21

- Some believe that scaphocapitate fracture syndrome is a variety of trans-scaphoid, trans-capitate, perilunate fracture-dislocation and represents the final stage of a greater arc injury with the potential of spontaneous reduction; however, the different degrees and directions of displacement of the capitate head imply that this injury does not have a unique mechanism.12,18,21

Imaging

- Plain radiographs may not show the extent of the median nerve lesion. This, combined with the rarity and complexity of these injuries, causes many diagnoses to be initially missed or incorrectly labeled as simple scaphoid fractures.18,21

- If plain radiography does not lead to a satisfactory diagnosis, a CT scan may be needed, especially if a complex lesion of the carpus is suspected.18,21

Treatment

- Some controversy exists about the optimal management strategy for a capitate fracture in scaphocapitate fracture syndrome, but conservative treatment—consisting of closed reduction and cast immobilization—may be appropriate for some nondisplaced fractures.21

- For displaced or comminuted fractures, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is generally considered the treatment-of-choice to reduce complications. The aim of treatment is reduction and fixation of both fractures to obtain bony union.

- A dorsal approach is most commonly used, while a volar approach is usually reserved for when decompression of the median nerve is necessary.22

- K-wires or compression screws are typically recommended to achieve fixation and reduce the risk for nonunion, and no significant differences have been identified between these two approaches.18,22

- According to the literature, it is recommended that reduction of the capitate precedes reduction of the scaphoid.

- Reduction of the scaphoid fragments is guided from the radial surface of the capitate and is not easily maintained if the capitate is not stabilized, as the proximal scaphoid fragment tends to displace into the gap of the capitate head.18

- Some authors recommended excision of the displaced proximal fragment of the capitate because of the possibility of avascular necrosis, but it’s been found that the capitate head can revascularize when replaced anatomically and immobilized until fracture healing.21

- Excision can also interfere with the function of the carpus and eventually result in degenerative arthritis. It is therefore advised that the capitate fragment is not excised, even if it cannot be fixed.21

- Cancellous bone grafting may be considered in some cases of bone loss.18

Complications

- Infection

- Avascular necrosis

- Nonunion

- Osteonecrosis

Outcomes

- For patients with scaphocapitate fracture syndrome, early surgical intervention with meticulous reduction and fixation of all fractures and dislocations present generally leads to a favorable result with minimal complications. Despite the severity of this injury, restoring normal anatomical relationships of the carpus can lead to a successful long-term functional outcome.18

- In one study of individuals with nondisplaced fractures, those treated surgically returned to work earlier and had better functional outcomes than those treated conservatively.21

- Delayed diagnosis and treatment of this injury has been found to result in nonunion with subsequent carpal arthritis and carpal collapse.21

Capitate dislocation and fracture-dislocation

- Dislocation of the capitate in any pattern is extremely rare. When these injuries do occur, it is usually concomitant with other fracture(s) and/or dislocation(s), meaning isolated capitate dislocations and fracture-dislocations are even less common.11,23

- Transscaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocation and perilunate dislocation are the two major patterns of carpal dislocation, in which the common feature is a dislocation of the head of the capitate from the distal surface of the lunate.19

- An isolated capitate dislocation is possible when a localized force is concentrated over the bone.23

- Significant energy is required to fracture and furthermore to displace the fragments in a capitate fracture-dislocation.3

- Rotatory dislocation of the capitate can be considered a combination of a dorsal CMC dislocation of the long metacarpal and a midcarpal dislocation at the luno-capitate articulation.19

Imaging

- Radiographic imaging should include posteroanterior (PA), oblique, lateral, and PA with ulnar deviation views.

- A CT scan may be necessary in some cases to confirm the diagnosis and characterize the orientation of the fracture fragments.

Treatment

- ORIF followed by immobilization is often necessary for dorsal capitate dislocations. After the immobilization device is removed, rehabilitation to regain wrist ROM should be initiated.23

- Capitate fracture-dislocations with unsalvageable devascularized fragments and significant ligamentous injury to the carpus may require wrist arthrodesis in which the remaining carpus is fused.3

Complications

- Infection

- Avascular necrosis

- Nonunion

Related Anatomy

- The capitate consists of a distal body that articulates with the index, long, and ring metacarpals at their respective CMC joints, the trapezoid on the distolateral/radial surface, and the hamate on the medial/ulnar surface, as well as a proximal neck and smooth, rounded head that articulates with the scaphoid and lunate bones at the proximolateral concavity. The dorsal surface is broad and wider than the narrow volar surface, which has a distinct prominence.5,13,20

- The cuboidal shape of the capitate provides it with inherent strength and makes it the rigid keystone of the carpus that bridges the intersection of the longitudinal and transverse carpal arches. As such, it is integral in the axial movement of the long metacarpal.3,13,20

- Ligamentous attachments of the capitate include the capitohamate ligament, radiocapitate ligament, radioscaphocapitate ligament, triquetrocapitate ligament, trapeziocapitate ligament, ulnocapitate ligament, a dorsal and volar CMC ligament, and two interosseous ligaments that attach on the lateral and medial surfaces of the capitate body. The head and neck have no ligamentous attachments, which leaves them vulnerable to rapid high-energy impact, bending, axial, shear, and torsion forces.5,20

- The only tendon associated with the capitate is the oblique head of the adductor pollicis tendon, which arises from several slips of the capitate.5

Incidence and Related injuries/conditions

- Fractures of the carpal bones have been found to account for between 8-18% of all hand fractures24,25 and ~6% of fractures overall.26

- Fractures of the proximal carpals are more common than the distal carpals, and the most commonly fractured carpal bone is the scaphoid, which represents 58-89% of all carpal fractures.24,25,27,28

- Fractures of the other 7 carpals are very rare and only account for ~1.1% of all fractures. The triquetrum is the most commonly involved of these bones, while fractures of the other carpals are even more rare and vary in incidence.29-31

- Due to its size and stability, capitate fractures have been found to only comprise between 1-2% of all carpal fractures;11,32,33 however, the true incidence of these injuries is not clearly known, as the diagnosis is often missed.7

- About 50% of capitate fractures are associated with concomitant osseous and/or ligamentous injuries, while the other 50% are isolated fractures.1

- One study found the incidence of isolated capitate fractures to be 0.3% of all carpal fractures, as most fractures are associated with additional wrist pathology like perilunate injuries and scaphoid fractures.7,32

- Another study found that 57% of initial X-rays failed to reveal an isolated capitate fracture, which shows why the reported incidence of these injuries is likely underestimated.6

- Capitate fractures occur most frequently in younger male patients between ages 20-30 who may be more prone to high-energy trauma than the general population. For this reason, coincident polytrauma is frequent in this population.5,7

Work-up Options

- Routine X-rays

- Standard wrist radiographs may not reveal isolated body or dorsal articular margin capitate fractures, especially if the fracture is nondisplaced. This is one of the main reasons many capitate fractures are undiagnosed.1,5,20

- Special X-ray views

- The dorsal tilt view, which is a PA projection with the central beam angled 25-30° towards the fingers and centered on the capitate, is useful when there is a suspicion of capitate neck fracture.34

- Radial and ulnar deviation views in the anteroposterior (AP) plane are also helpful for making capitate fractures more evident.7

- Carpal tunnel view34

- CT scan

- May be necessary for occult capitate fractures that don’t appear on plain radiographs. In these cases, a CT scan in the coronal plane for transverse fractures and in the parasagittal plane for articular margin fractures is recommended.1,5,11

- MRI

- May also be needed for occult capitate fractures.5,11,12

- MRIs are helpful for achieving a prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment regimen, and for delineating fracture displacement and associated ligament injury.2,7

- MRIs are also useful for predicting healing potential of transverse body fractures by visualizing the vascular status of the capitate head.1

- Isotope bone scan

- Another imaging option for occult capitate fractures when radiographs are inconclusive.5,11